Monday, August 24, 2015

Reflections on Mahatma Gandhi as his Grandson Arun Gandhi approaches the City Club podium

Every Martin Luther King, Jr. Holiday weekend, since my now-11-year-old triplet boys were six, our family has gathered to watch the epic film “Gandhi.” Dr. King, the boys have seen, absorbed from Mahatma Gandhi the non-violent-action techniques applied in the American civil-rights movement. And Gandhi’s tactics were forged from his experience with blacks and other oppressed communities during his time in South Africa (kind of a nice circle there).

The boys now quote freely from the movie—from the absurd (“Mr. Gandhi will find it’s going to take a great deal more than a pinch of salt to bring down the British Empire!”) to the profound (“An eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind.”) With each viewing, the boys’ historical understanding of both the challenges Gandhi faced and his accomplishments grows deeper.

Translating that understanding into a contemporary application of Gandhi’s lessons is more challenging, however.

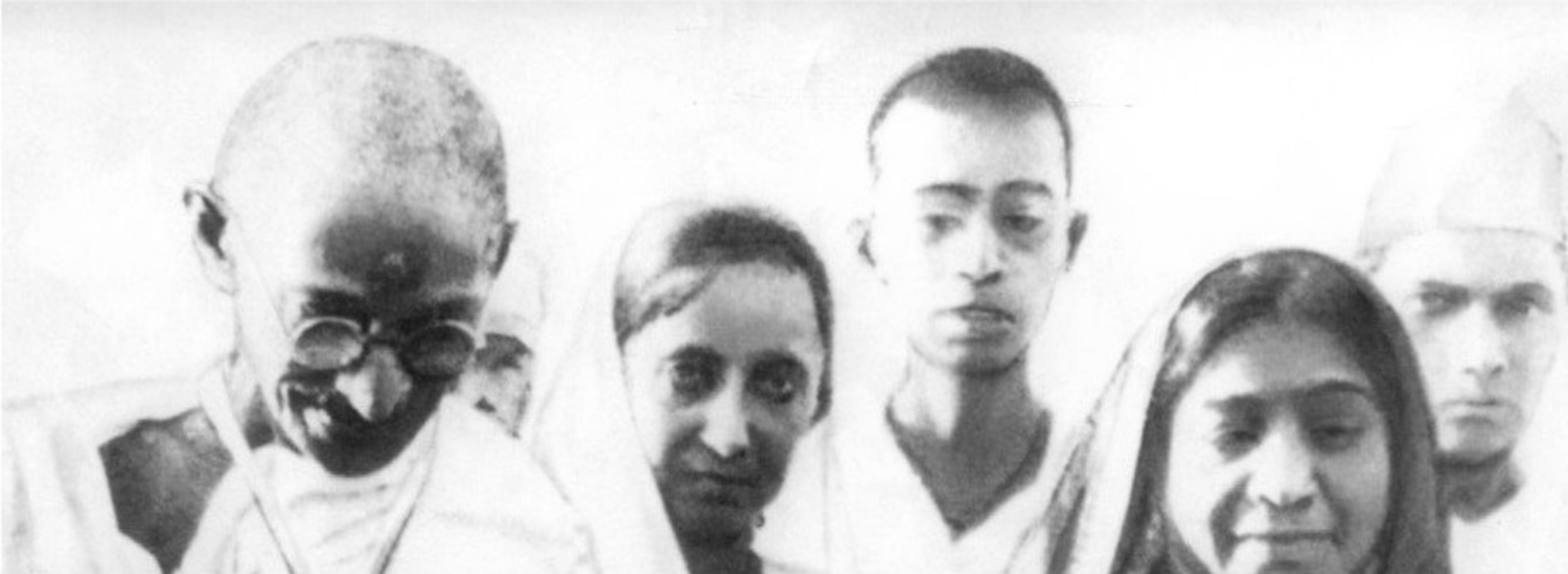

Gandhi’s name, after all, instantly evokes the image of an emaciated, loin-clothed, saintly figure who, through his Satyagraha (“truth force”), dedication to non-violent protest, and inherent goodness, compelled the British to see the error of their own ways and quit India in 1948.

This mental caricature of Gandhi, however, belies the fact that he was a shrewd political strategist whose approach transcends time and place, and can work effectively in other contexts. “If we label Gandhi a perfected being,” Gandhi scholar Mark Shepard notes, “we lose our chance to view his life and career critically and to learn from his mistakes. Besides, if people see Gandhi as a saint, they’ll think he’s ‘too good for the world,’ and they won’t take his example seriously as a model for concrete social change.”

We can apply Gandhian techniques at the macro level—in pursuit of broader social-justice goals—or apply them at the micro level in our day-to-day professional and family lives. Gandhi’s approach takes the objects of persuasion over an emotional curve he summed up as, “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.” But even winning, in Gandhi’s eyes, did not entail the adverse parties “losing.”

For the key when applying Gandhian techniques is to apply them not to humiliate one’s opponent but to bring greater understanding—or at least acceptance and correction of the injustice. As Shepard explains,

Satyagraha—Gandhi’s nonviolent action—was not a way for one group to seize what it wanted from another. It was not a weapon of class struggle, or of any other kind of division. Satyagraha was instead an instrument of unity. It was a way to remove injustice and restore social harmony, to the benefit of both sides.

Satyagraha, strange as it seems, was for the opponent’s sake as well. When Satyagraha worked, both sides won.

***

You may wonder, how did Gandhi himself come to this amazing attitude? He said it this way: “All my actions have their source in my inalienable love of humankind.”You see, love for the victim demanded struggle, while love for the opponent ruled out doing harm. But in fact, love for the opponent likewise demanded struggle.

Why? Because by hurting others, the oppressor also hurts himself.

Coming to believe in this interconnection between villain and victim is difficult. The idea is not that oppressor and oppressed will necessarily sing “Kumbaya” together—or, as Gandhi said of the British, “When they leave, we want to see them off as friends.” The idea is to change the offender’s behavior and attitudes at least to the point where fewer injustices will be inflicted in the future.

My civil-rights law firm often borrows tactically from Gandhi by highlighting a particular injustice in such a focused and public manner that adversaries engaged in the injustice first attempt to ignore us, then mock us, then fight us, and then eventually it is too late and they must relent. The pattern is the same each time.

And as Mahatma Gandhi’s grandson, Arun, points out in his public lectures—including I would expect at his upcoming City Club of Cleveland appearance—Gandhian techniques can be applied in family life to drive moral lessons home. I won’t spoil Arun’s story about how his father taught Arun not to lie, but it is powerful.

Gandhi’s core lesson is that there is always a tactical way, even in the midst of extreme conflict, to move toward justice. “When I despair,” he said, “I remember that all through history the way of truth and love have always won. There have been tyrants and murderers, and for a time, they can seem invincible, but in the end, they always fall. Think of it: always.”

Subodh Chandra is a City Club member and Managing Partner at The Chandra Law Firm, LLC.

photo credit: Wikimedia Commons